Drivers are inattentive at least half of the time when turning right, and 65% of the time they don’t register a person on a bike or motorcycle (or people walking). “This phenomenon—a person’s failure to notice an unexpected object in plain sight—is known as “inattentional blindness.” It’s the reason why a driver might look right at you, but cut you off anyway. ” The old “I didn’t see him”, or “she came out of nowhere” excuse is actually the truth. The driver really didn’t see the woman walking into the intersection because he didn’t take the time to look slowly and carefully from side to side to bring the person into the center of vision.

Taking a deeper dive, here’s the science, in an article by an RAF pilot explaining that our eyes were not designed to see detail from the periphery. So unless a driver is looking intentionally, and directly at a person walking or riding a bike, “visual acuity is about 1/10th of what it is at the centre.”

Now that we know that drivers don’t see people outside of the vehicle, let’s add driver entitlement, and the embedded belief that roads were designed for cars, and we realize the very real danger to people walking and riding bikes.

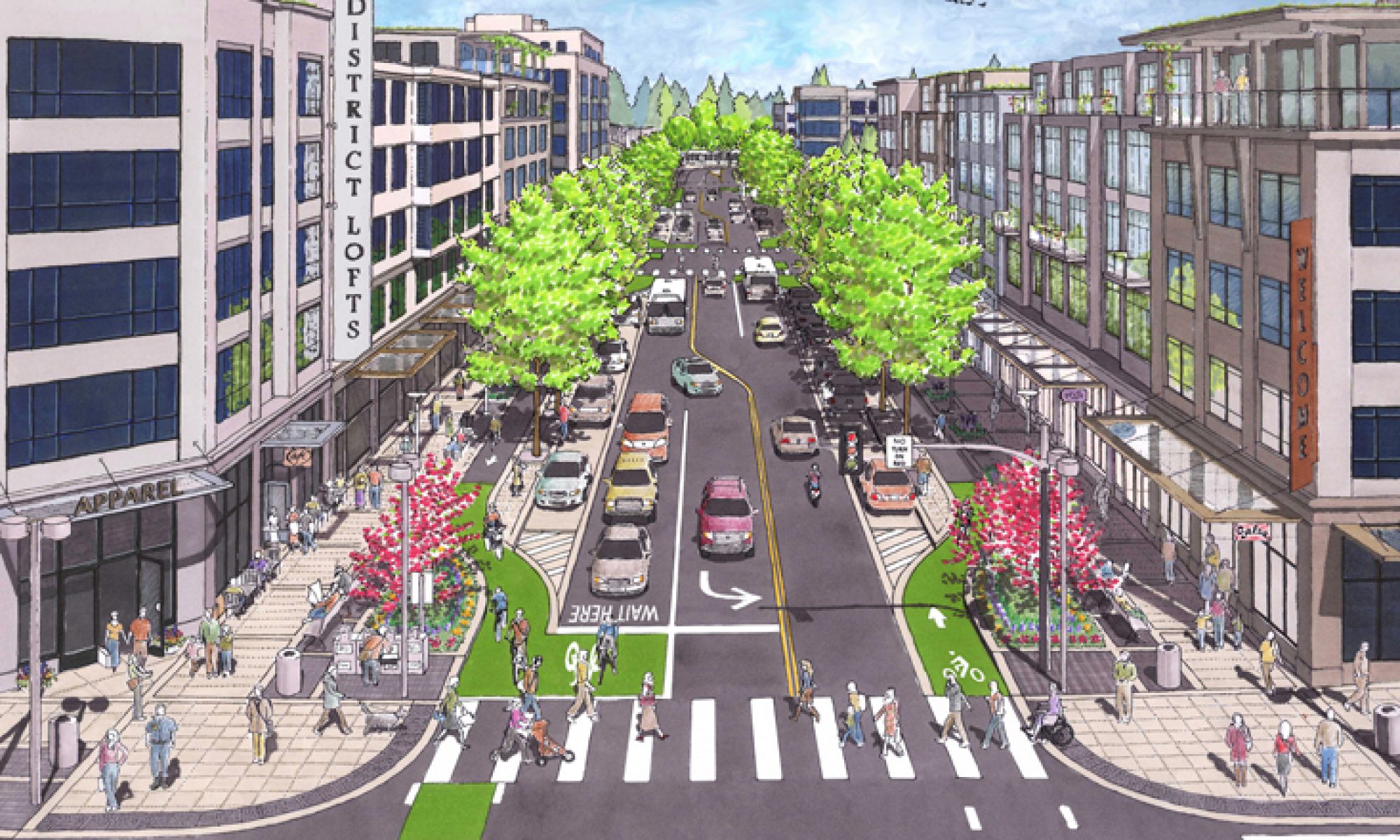

It’s wishful thinking that drivers will change habits, so we need to redesign roads so that drivers have to slow down, install better and safer infrastructure for people walking and biking, and redesign our cities for less car dependency; cities are for people, not for cars.

The Surprising Reason Why Drivers Don’t ‘See’ Cyclists

The Surprising Reason Why Drivers Don’t ‘See’ Cyclists

NEW RESEARCH EXPLAINS WHY CYCLISTS CAN ENTER A DRIVER’S FIELD OF VISION BUT STILL GO UNSEEN—A PHENOMENON KNOWN AS “INATTENTIONAL BLINDNESS”