In most American cities, bike and walk advocates beg for validation and funding like a “charity case”, and end up getting acknowledged and funded as such, resulting in insufficient or piecemeal infrastructure. We commonly see bike lanes that abruptly end, unprotected bike lanes that don’t offer leading bicycle intervals or leading pedestrian intervals (LPIs and LBIs), or safe left turns, and painted lines “that put cyclists between fast-moving traffic and parked cars with doors that capriciously swing open”, so only experienced riders will brave them, and discouraging new riders. This kind of bike and walk design and implementation continues to give drivers the sense of entitlement that roads are intended for them, and discourages people from riding bikes, scooters, and walking, thereby creating more traffic congestion perpetuating the inherent safety, health, and environmental issues.

As advocates for safe, complete streets, do we dare to go big to make environmental, social, and safety gains we hope to achieve? If American bike and walk advocates are “pitching ourselves as a niche, special-interest group”, we are “tacitly agreeing that cars are and should be the dominant mode of transportation…”

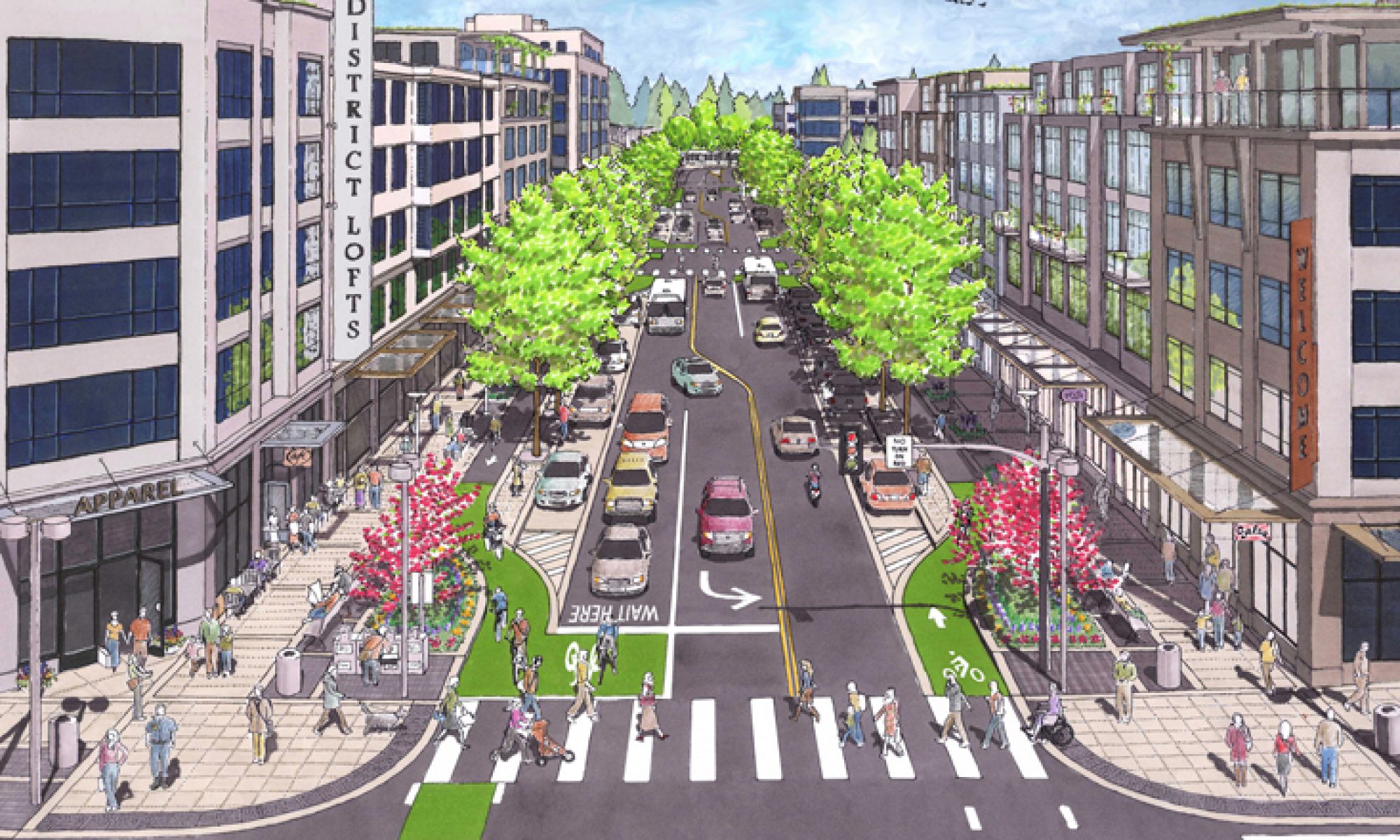

The auto industry has dominated since the 1930s by promoting plans for highways and streets for cars. Asbury Park is a 1.4 mile square city, where we have envisioned a plan for biking and walking, a network of infrastructure that can be a model for cities all over the US. Let’s do it big. Onward to 2020 and beyond!

Why We Need to Dream Bigger Than Bike Lanes

In the 1930s big auto dreamed up freeways and demanded massive car infrastructure. Micromobility needs its own Futurama—one where cars are marginalized.

“More often than not, bike infrastructure is created reactively. Typically in response to a collision or near collision with a car, an individual or advocacy group identifies a single route that needs better infrastructure. We gather community support and lobby local officials for the desired change, trying as hard as we can to ask for the cheapest, smallest changes so that our requests will be seen as realistic.

What’s the problem with this model?

It’s like imagining a bridge and asking for twigs—useless, unable to bear any meaningful weight, easily broken. And it’s treating bike infrastructure like a hopeless charity case.

This makes bike infrastructure seem like a small, special-interest demand that produces no real results in terms of shifting to sustainable transportation, and it makes those giving up road space and tax dollars feel as though they are supporting a hopeless charity.

But when roads, highways, and bridges are designed and built, they aren’t done one neighborhood at a time, one city-council approval at a time. We don’t build a few miles of track, or lay down some asphalt wherever there is “local support” and then leave 10-mile gaps in between.”

Read it: